Mike Ormsby is a British writer and former BBC journalist, World Service trainer and musician. In December 2013 he published his first novel, Child Witch Kinshasa, about so-called child witches in Kinshasa, Congo – as seen mainly by Frank Kean, a journalist who lands in a strange place and tries to discover its “secrets”, to understand a completely different world (see synopsis and excerpts here). As I was reading this, absorbed, the second part of his novel was published – Child Witch London.

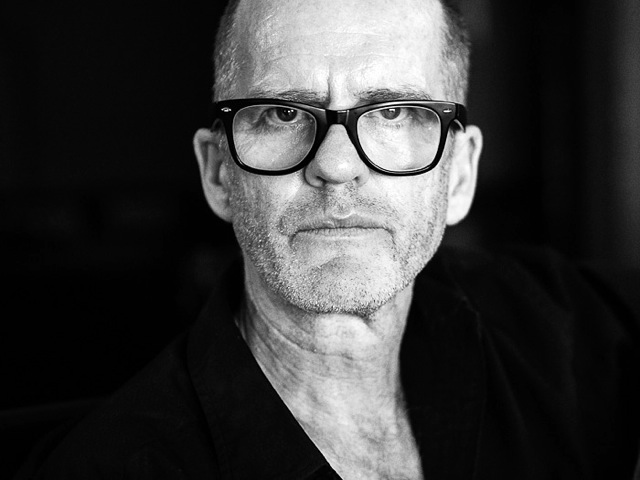

The novel is a very interesting read, so I wanted more. Therefore, I spoke with Mike Ormsby, who is a very warm and friendly writer (and by the way, he has his home here, in Romania), about the real story behind the novel, about his writing process, about the importance of influences and experiences for a writer, about travel, discovering new worlds, about style and the construction of characters, about Congo and ‘child witches’, about Romania and his strong bonds with our country and many, many other things, as you’ll discover below.

Child Witch Kinshasa is your first novel (and even a lengthy one!) after a short story collection (Never mind the Balkans, Here’s Romania) and a children’s book (Spinner the Winner), so it’s a little bit surprising the fact that you barely feel this, here and there. Did you rewrite fragments of it? What did you learn about writing in this period and you would like to tell the others?

If you mean what advice would I give to fellow writers, I would say: keep going, no matter what, and finish the job. I started writing Child Witch in 2003, and had to put it aside for other, shorter projects. For example, in 2007, I was commissioned to write a film script about HIV, and some booklets about safe sex for the Rwandan army. In 2007, I wrote Never Mind the Balkans, and Editura Compania published it in 2008. But Child Witch was always in the back of my mind, bubbling away like a pot of ciorba on a stove. I would peep under the lid, sometimes, to check :).

Eventually, I decided, “I have to prioritize this, or I’ll never finish it.” I’ve worked on it all over the world – America, Asia, Europe and Africa. Did I rewrite fragments? Eli, are you kidding? I wrote about ten drafts, re-working it, to make it flow. The hardest thing in the world is to make something look simple. I rewrote the first chapter many times, because I wanted the reader to experience exactly what I experienced on my first night in Congo. In real life, my wife Angela Nicoara was with me, and we stood together on our hotel balcony, at about 3 a.m., listening, staring into the darkness and wondering, “What is that noise? What the hell is going on, out there?”

Knowing a few things about your career, I was tempted, when I was reading the book, to consider Frank your alter ego, even if there are a few differences (for example, his family). Did I make a mistake? Can we consider your book a non-fictional novel?

No mistake! If most autobiography is fiction and most fiction is autobiography, then yes, Frank’s experience is based closely on what Angela and I experienced, working and travelling around Congo, together and alone. But, when I created Frank, I needed him to be ‘not me’, so I decided he should smoke (I do not) and have curly blond hair (I do not), in order to create ‘distance’. I also made him a compulsive traveller, who counts his ‘countries visited’ and always wants one more. That’s based on a friend of mine and I used Frank’s ‘travel’ obsession to help drive the plot.

Did your experience as a journalist help you in having such a clear, direct, concise (despite its length!) and funny style of writing?

Thank you for the compliments and, yes, you are probably right. The skills one develops as a radio journalist have influenced the style of my writing. But, perhaps more significantly, I was also a radio journalism trainer, and have spent years analyzing and teaching a ‘direct’ style of writing. I like to present information in a clear and chronological way. I like my action on the page, not ‘three weeks ago’. I avoid the pluperfect tense whenever I can, and, more than anything, I try to avoid ‘wooden’ back story – exposition can be hard to get right, for any writer who cares about it. The disadvantage of having a short and direct style is, as my young, bookworm nephew once told me, “Your sentences are too short, please can you write some long ones?”

By the way, I’m glad you find the novel funny, other readers say the same, and I think humour helps, in this case. But that’s not because of my journalism background; it’s because Liverpool is full of dry-witted comedians, at every age. Jokes fly fast and you develop a quick sense of humour as a kid. I offered some Russian chocolate to a seven-year-old while I was home recently, and he said, “Has it got any vodka in it?”

There are three parallel stories in the book: Dudu’s story as seen through his eyes in his native region, Frank’s point of view, the stranger, the journalist who discovers Congo’s “wonders” and Ruth’s part – Frank’s wife – together with her children’s back in London. I didn’t spend time counting which narrative thread is longer or to see the frequency, they all seem equally important in creating the bigger picture.

But I wondered how did you manage to slide between the chapters and different perspectives? When did you know that it’s time to switch to another point of view?

These are great questions, Eli, thank you for reading so closely. Weaving the various narrative threads was difficult because I had to consider time, location and plot. I tried scribbling on cards in neat columns on the floor, but our cat had other ideas, of course. So, I tried using Excel, but I’m useless at that. Eventually I settled on Stickies.app, which worked well, until I changed Macs and lost all my notes, which were not so ‘sticky’ after all, aagh!

Sometimes I knew exactly when to switch between narrative threads, but sometimes it was hard to decide: should I divide a chapter? Combine two in one? The chronological aspect was a challenge because I wanted the story to happen in real time. I’m lucky because I live with my editor, Angela, who reads a lot of fiction. She read my MS many times, and gave good advice: “No, stop here. Cut this, move that. Boring. Who cares? Not me.” She is deadly with a red pen. Sometimes we’d disagree, and she’d say, “Whatever, it’s your book.” Then, I’d go away, read her cuts and think, “Hmm, this reads better, she’s right.”

“No wonder people lose hope. There’s a material and spiritual vacuum, once the shooting starts” says one of the secondary characters in the novel to Frank, the journalist curious about the child witches phenomenon. Can the war be responsible for all the atrocities that happened in Congo?

Directly and indirectly, yes. Let’s consider the context: GDP fell steadily over a thirty-seven year period from 1960, until the end of the First Congo War (1996-7), when it was down 65%. In other words, the country was falling apart long before the Second Congo War (1998-03), which killed 5.4 million people – mostly from disease and starvation, not bullets. During that second war, nine countries and twenty groups fought for land, diamonds, gold, bauxite, you name it; they got rich selling raw materials to Asia and beyond. The military factions did not want peace, just more control and money. That kind of war cracks any society open, and, in 2002, when we arrived, Congo was a failed state, paralyzed by conflict and greed.

At the bottom of the social and economic abyss were desperate, uneducated people who needed someone to ‘explain’ it all. In Congo, they’ll often believe a charismatic pastor, who says, “You suffer because of sorcery! A witch is among you! But I can find them, for a small fee…” When a ‘witch’ is identified, they can become the scapegoat for a community’s fear and frustration, and if someone suggests that a beating will chase Satan away, the beating begins. Worse can follow. So, war creates the conditions for paranoia to thrive.

Child witches in Congo – photo credit

Do you know what’s the situation now in Congo? Did something change?

From the perspective of so-called sorcery, there has been a significant change. In 2009, a new law was passed, and anyone who accuses a child of sorcery can face between one to three years of penal servitude. So, that’s progress. But a question remains: how many ordinary people know of that law, and even if they do know, how many would dare to invoke it? Consider: if you accuse a pastor of being a bully, the pastor can easily defend himself by accusing you of being a witch too. Things change very fast in Congo. We soon learned that you can find yourself in trouble very quickly.

From a general perspective, the Congolese do not seem too impressed with their current leaders. I think most are weary of broken promises, as a character in my book says. Sure, little by little, as time moves on, things will probably get better, and Congo’s vast natural resources mean it will always have incredible potential, especially if initiative and hard work are rewarded. But progress is undermined by the Big Man system of government, poor physical infrastructure, shattered healthcare and education, and, of course, by the simmering military problems in the north east. Some analysts say Chinese investment will change Congo’s demographics and culture, in ways that might help the economy if Chinese workers marry locals and settle. Business as an infectious bug? We’ll see.

Child witches in Kinshasa – photo credit

“That’s life as a writer. It’s just a job, but one you can never leave, like Hotel California.”

During your novel, we meet the evil under many masks. In writing literature, what’s the worst that can happen, from your point of view?

I’ll answer in two ways. First, the practical aspects. My wife and I have a ‘nomadic’ life. We’ve lived and worked in 18 countries in the last 18 years, we rarely stay in the same place for more than a year. In some ways, this is perfect for a writer, because I see different places and absorb cultures, so yes, all those ‘travel’ clichés apply. But I also need silence, solitude, and a routine, and that’s not easy to find, say, living in Khartoum, in the middle of a sandstorm. Or even in Romania – I lived in Bucharest for a summer, while Angela was in Darfur, and I was trying to write Child Witch in a small flat with traffic and road works below. So, I relocated to a bench in Izvor Park, and thought, I’ll write by hand for a few weeks, this will be my office: sunlight and fresh air, perfect. A few days later, a lorry drove into my bench and squashed it flat. I was unhurt, but upset. It seemed an omen!

Second, from a technical aspect, the worst thing is when a line of dialogue, a scene, a passage or a chapter does not work and I cannot see why. Or, I’ll just be falling asleep and I’ll get an idea that I must write down, so I’ll put the light on, then I can’t get back to sleep. Or, we’re having dinner with friends and someone will say something that I must scribble down. It’s a compulsion, full stop. I’ll be walking down the street, and Angela will ask, So who are you talking to? That’s because I’ve been muttering dialogue.

That’s life as a writer. It’s just a job, but one you can never leave, like Hotel California. But, sometimes, I’ll get a nice surprise without trying, and wake up with a line in my head, for example: “I’m not interested whether I’m better than you, only whether I’m better than yesterday.”

Picture from the author’s personal archive. Pages written in Izvor Park

On the other hand, does your literature offer a solution for the issue of child witch (almost an universal one) or wants just to raise awareness?

I doubt that a novel can offer a solution for a serious social problem, such as the one I describe in Child Witch. At best, a novel can raise awareness and pose questions, and I hope mine does. I think a serious writer records – and questions – the present for future generations. A member of Unicef Congo told me he learned a lot from my book, which surprised and pleased me.

But I visited some schools in the UK recently, to present my work, and a young student asked me, “Why didn’t you write about something nice?” I asked him if he had heard of a boy named Oliver Twist, and I explained that Dickens could have written about how ‘nice’ life was in Victorian England, but instead he often wrote about how unfair it was, and that’s why we know about Oliver Twist, whose dilemma still pricks our conscience and makes us remember that kids have rights, they deserve something better than poverty. Did Dickens offer a solution? Only to his story, and perhaps all writers try to resolve their stories, as I tried to resolve mine. But we cannot resolve the world.

Exorcism – photo credit

At the end of the book, you say a few words about the background of the story, how you came across it and decided to do something about the matter of child witches. First of all, helped by your Romanian wife and editor, Angela Nicoara, you made a documentary and a music video. Can you sum up the story for the readers? When did it strike you that you can also write a book with this subject?

I wasn’t ‘helped by’ Angela. She knows how to shoot and edit film; I don’t; so if anything, I was her assistant. We worked as a team in Congo. Same for this book – every serious writer needs an editor, someone who understands and will contribute their time, their concentration, their heart and soul.

But, to answer your question: by 2002, I had wanted for a long time to write a novel, about something, anything, but could not find a theme or central character that interested me. That all changed the day we met Kilanda, the young boy at the start of our documentary film. He had been so badly burned, by an ‘exorcist’, that he could not speak to tell us his story. So, on the drive home, I decided to imagine it, to create it, to write it. I knew this would take a long time, because it would require a lot of research, other characters, locations, and a sub-theme. But little by little, my plan took shape – a novel set in Africa, told from multiple perspectives, in real time, which would ask: why would a Congolese person accuse a kid of sorcery? What happens if the kid is kicked out of home? How do they survive? What would happen if a foreigner tried to help?

To answer those questions, I blended fact with fiction, based on our time in Congo. I looked for a Congolese advisor, to help on matters cultural, linguistic and geographic, and found Félicien Wilondja Basiku-Ngoma. Or rather, a Romanian friend in Norway found him! I could not have written my book without Angela and Fély. Writing a novel is like being in a band or a sports club: you need a good team.

To hear the song from chapter 49 of Child Witch Kinshasa, please click the link above.

Will Child Witch Kinshasa be translated in Romanian? What future plans do you have with the volume? Maybe a movie? (it’s very visual!)

I would love to see a Romanian translation, yes, but it’s a long novel and the cost would be astronomical. So, I’ll need to find either serious financial support, or a talented saint who’ll translate 900 pages for whatever we can afford. To be honest, our priority is a French translation, because we want people in Congo to read the story. Those Congolese who have read it in English, loved it.

As regards a movie, I think any writer would love to see their work filmed. Two of my scripts have been filmed and, yes, it’s a magical experience when you see characters who used to live only in your head, now walking and talking onscreen. Truly, movies are benign sorcery. Several readers have told me, “This novel is so visual, just like watching a film.” That might be because I’m careful, to the point of obsession, with exposition. If I start reading a novel and I can hear the author’s typewriter, I stop reading, usually on page one.

Among other writers, you mention, at some point, Hemingway. Tell us a few authors that influenced you or that you love.

One of my characters likes Hemingway, I don’t. I read twenty pages of Farewell to Arms, and said farewell to Hemingway. One reviewer said I write like Faulkner, which is nice, but I cannot read him either. I enjoy James Joyce for his economy in a minor key (Dubliners). I like the first hundred pages of any Elmore Leonard, for dialogue and character, before his plot drowns my pleasure. My favourite novel is L’Etranger by Camus – short and easy on the eye, as if he wrote it on a pack of Gauloises at lunchtime. I like Yukio Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell With Grace From the Sea, and Guy Vanderhaeghe’s The Englishman’s Boy. I enjoyed Colm Toibin’s recent The Testament of Mary, which has an interesting premise. I like Hilary Mantel, Sebastian Faulks, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Don de Lillo, Cormac McCarthy, Julian Barnes, Roger Smith, Robert Harris, and Nelson DeMille among others.

To be honest, I don’t read much modern fiction; I find it overrated and I can’t ‘turn off’ – I sit there looking at the nuts and bolts. So, I usually carry a copy of The Economist, or The New Yorker. My worst nightmare is being in a supermarket queue with nothing to read. When it happens, I read the ingredients on a packet of M&Ms, or whatever is on sale.

Last night I found some new editions of Caragiale, on Kindle (English translations by Cristian Saileanu, not bad). I like Candide too, Voltaire’s pretty funny; he’s got a wicked tongue. But Shakespeare is the man; he says so much in so few words. I read this recently, and could only think of Crimea: “I speak of peace while covert enmity, Under the smile of safety, wounds the world.”

“I would recommend my novel to anyone who likes short chapters, clear sentences and interesting ingredients.”

I read some of the reviews that some readers wrote about this book, Child Witch Kinshasa. Many of them ended with recommendations as follows: ”this book is for anyone interested in Africa, journalism, disability or just a good story”. Let’s imagine, for a minute, that you didn’t write it, you just read it. To whom would you recommend the Child Witch book?

I would recommend it to anyone who likes short chapters, clear sentences and interesting ingredients. Oh, also, it helps if you are curious about foreign places. One Romanian publisher warned me, ‘Romanians are not interested in Africa.’ I could only disagree, and reply, Vom vedea, shall we?

Another child witch and a pastor trying to get out the evil – photo credit

The second part of Child Witch, settled in London, was just released on the first of March. Can you tell the readers, in a few words, what does it come next? What should they expect to happen?

As I developed my story, set in Congo, I felt something was missing. I did not want just to write about Bad Things In Africa. I needed balance, a twist in the plot, something to turn the tables, as we say, on Frank, the British fellow who tries to help the street kid. Eventually, I got it, and it came as a new question: what if this liberal-minded, white, middle-class Brit, and his family, must face the same questions as a poor and superstitious family in Congo, IE. Who is this kid really? Does he have strange powers? Why are things going wrong in our home? Is the kid responsible?

Once I got that second angle, that twist, I knew I had my novel. I knew the story would be longer, but it would also be more balanced, because it would say: when we point a finger (at Africa), three fingers point back. So, that’s what to expect; the second part of the novel, set in London, asks: what if…?

I just found out that you recently were to your old high school Maricourt, England, to speak with sixth formers about Child Witch books. Do you find your books appropriate for such a young category of readers? Let’s not forget that children are tortured here.

It’s a valid question! But actually, there is very little ‘torture’ in my novel and, when it comes it’s over quickly. Also, I emailed the teachers in all the schools before I visited, and explained in detail what the book was about. I sent them Chapter 23, where two adults try to sexually abuse two boys (I’ll spoil the plot if I say more, but I was more concerned about that scene). The teachers looked at that chapter and advised me accordingly.

Also, don’t forget that students can see, on the Internet or in a cinema, images that are far more violent than anything in my novel, which exists only as words on a page. Plus, I was there to explain the social context, show them our two videos, and answer their questions. The response was interesting. Some were too stunned to say anything; others were very interested and now plan to write assignments for their exams on the subject. So, my novel has reached new readers and some are asking questions. I must say, in Azerbaijan, expat kids as young as ten were desperate to read Child Witch Kinshasa, once they saw the cover. I made sure they got their parents’ permission first.

You have strong bonds with Romania. What are the first three things that come to your mind when somebody names it? And by the way: what do you know about child witches here, in Romania? Did you ever think to write something about it?

I was in Liverpool recently and found the first postcard I sent in 1994 from Craiova, as a BBC journalist, to my parents, which says, People very warm and friendly. I’m coming again, no mistake. That’s always the first thing I think of: the friendly, witty people and how this country draws you back. It’s my adopted home and I hope one day to stop travelling and settle for more than a few weeks at a time. Second, I love how Romanian families have links to the land, to nature, and to real food. If you ask the average Brit or American, can we make soup? They’ll say, sure, open that tin. I’ve learned a lot from Romanians about that side of life.

As regards sorcerers, the only ones I have met in Romania are adults. They know clever spells. They open bottles of tuica and say, Try this one, have some more! Then the world starts to spin and you hop home like a frog.

But seriously, I have several ideas for what to write about next. One idea is a short novel set in Romania. I have my title, characters, and the story. It’s in my pot, bubbling away. I just need a quiet place to work. Perhaps a wooden bench in a nice park?

Credit photo for the main image: Cosmin Bumbuț