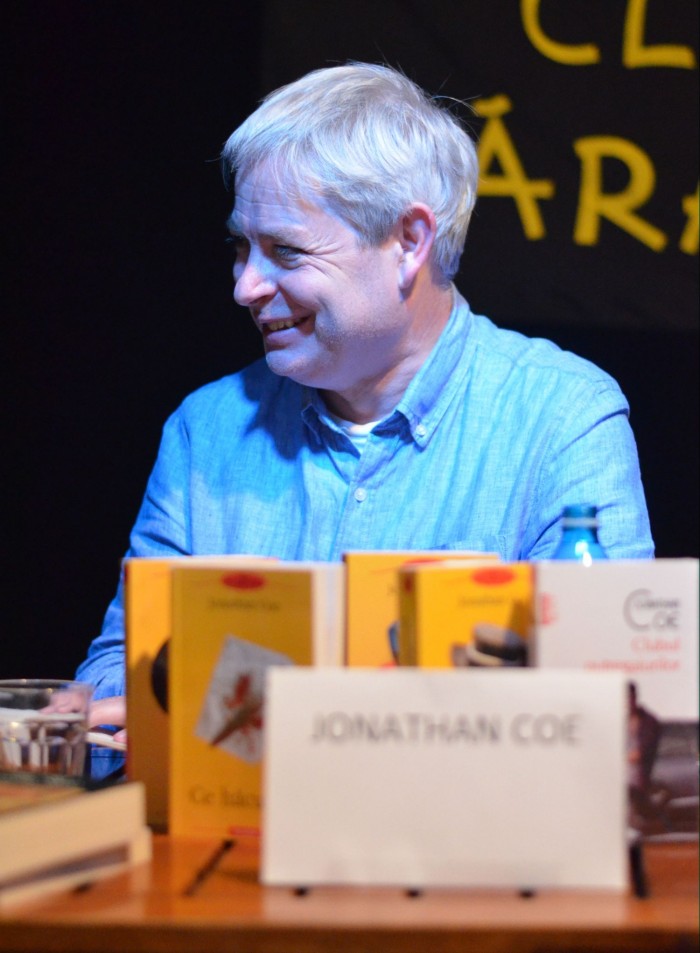

The first night of the International Literature Festival in Bucharest (5-8 December 2012) was dedicated to Will Self and Jonathan Coe, who made quite an impression. While Will Self was very flamboyant and colourful, Jonathan Coe displayed a somewhat cold, elegant, but witty attitude. Jonathan Coe is best known for novels such as What a Carve Up!, The House of Sleep or The Rain before it Falls. He is also passionate about music and explains why it is important for a writer to get his inspiration from the reality surrounding him.

Before becoming a writer, you were interested in music, you even played in a band. How did music influence your writing?

I was only ever an amateur musician. What I got from my interest in music, jazz and classical music was the interest for structure, for form, which is quite unusual for a British writer. What mostly gets discussed is style, but for me, the exciting part of a novel is the planning and the shaping. I think I have an approach to the novel which is kind of musical, in the sense that form and structure are very important to me and in a kind of jazz idiom, within those structures I try to leave room for improvisation, because if you plan a book completely before you start writing it, it becomes kind of dead.

Do you still play?

Yes, I do… I used to have real fantasies about becoming a musician, but in the last ten or fifteen years, I’ve become friends with a lot of musicians, I’ve watched them working and I understand now that I don’t have the talent or the dedication, that it can only ever be a hobby for me. I like to write pieces of music for myself, but I don’t think I’ll ever share with the wider world, because I don’t think it’s good enough.

You also worked on a very interesting music experiment called Say Hi to the Rivers.

As you know, fewer and fewer people are reading, particularly young people, they go online to get their entertainment. This presents a problem, but also presents a challenge, an opportunity of new ways of combining different art forms. I always loved music, but I was always interested in what happens when the words are spoken in the form of music. I think this goes back a long way to my childhood, when I was very interested in films. It was the 1970s, so there were no video recorders, but I used to record the soundtrack and I used to listen to films in bed, at night. So my ear became very tuned to the relationship between music and film and the words, the dialogue, without the visuals.

That interest always stayed with me and I experimented with giving readings of my work with musicians, with music specially composed to go with words. And I thought it would be interesting to go a little bit further and I talked with my friend, Sean O’Hagan, who’s the composer and singer of High Lamas, he writes music which is very filmic, emotional, it’s perfect for talking over. We did a theatre piece together, where I took 60 minutes of his music, songs that were mainly instrumental and I wrote a text for three performers. It was really an extension of the idea of giving the reading good music. But it’s a difficult piece to organize productions because it’s expensive: ten performers, seven musicians and three actors, it requires a lot of rehearsal, so we’ve only done eight to ten performances, I hope to do it again.

Your books have a musical structure and many of them develop very strong imaginative worlds, such as The House of Sleep. Reality is often interchangeable with dreams and fantasies. How do you see this relationship between reality – or what we understand by “reality” – and dreams?

I don’t have a theory of dreams, I’m not Freudian, I don’t believe actually in dream interpretations. But even though this is a part of our imaginative life that we don’t understand, that doesn’t mean it isn’t important, in fact that perhaps makes it more important than anything else.

It’s been a disappointment for me as I grew older, since writing The House of Sleep, that my dream life is diminished. I don’t have the kind of vivid dreams as I did when I wrote this book. It’s a scene in the novel where Sarah confuses reality with dreams, which used to happen to me all the time. I remember when there was a time when I would wake up from a dream convinced that one of my best friend’s mother had died and I sat down and wrote him a letter of condolence and I was just about to seal the letter and put it in the post when I started to think: did I dream that or did it actually happen?

So I phoned him up and he didn’t mention that his mother had died, so I guessed maybe it had been a dream, so I never posted the letter, but I always thought that it would have been really bizarre for him to have received that letter. Is not that dreams are trying to tell us something, but it’s important to attach significance to things that we don’t understand.

You also write about political aspects in contemporary England. Why do you think it is important to tackle them?

My feeling now is that it doesn’t really matter what you write about, it’s how you write, truthfully and honestly and in a way which encourages people to think more about the world around them. I don’t know if I will write another political satire like What a Carve Up! As life goes on, it becomes harder to make jokes about political injustice. The tone of What a Carve Up!, which is what people liked about it so much, the kind of dark comedy of the book I find hard to write like that nowadays, because fewer things make me laugh.